During her junior year of college, Pam Royes made a decision that everyone who knew her thought disastrous. She rode off into the wilderness — literally, not metaphorically–with a Vietnam vet named Skip she had met only days before. Within weeks, she had suffered a bullet wound and watched her mare fall off a cliff. The story goes on from there, itself a cliffhanger, the sort of thriller where you find yourself saying over and over, “Don’t go into the barn. Don’t go into the barn.” But go into the barn she does, repeatedly, and this is the story of the fallout of those many decisions. Wherever you think this might lead, I suspect you will be surprised, and I won’t spoil it here. The story is a thriller but not a usual one, and among its many distinctions is the beauty of its prose, which renders the sensuality of a life lived in the wild and on the edge with tender amazement.

As a form, the memoir has been around since Augustine wrote his confessions in the 4th century AD. It has ebbed and flowed in popularity and answered various purposes, from confession to redemption to excitement to exhibitionism to revenge. At its best, it is provocative and illuminating, and Temperance Creek is both.

The field of evolutionary psychology posits that the ability to tell stories is an evolutionary advantage and may be one reason homo sapiens have survived where other hominids have not. Stories provide a way to learn from others’ experiences and transmit information over distance and time. We remember information embedded in stories more accurately and in much greater detail than when we receive it simply as fact. As we throw ourselves into a story, we can try on other identities and experiment in an infinite number of environments within the relative safety of our own imaginations. Stories are so central to the human experience that Jonathan Gottschall, author of The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, suggests that our species could accurately be called homo fictus. The neuroscientist David Eagleman proposes that stories are as essential to our survival as our DNA.

In other words, stories provide a user’s manual for the world. This may be one reason that memoir has enjoyed ascendancy in the past three decades, a period of economic, social, political and environmental upheaval during which everything from gender identity to the weather has been in flux.

It is said that fiction tells a truth while nonfiction tells the truth. As we know, truth is problematical. Memoir depends on memory and anyone who has ever told a story in the presence of a sibling or a spouse knows that memory is plastic and subjective. But as we try to find our sea legs on turbulent waters, we hunger to hear from those we sense we can trust who have returned from the storm.

Trust is the key word. Over the past several years, the genre has suffered its share of scandals and embarrassments that have left devotees of the form feeling lied to, manipulated and wary. But then a story comes along that is earnest and fresh, an act of generosity rather than of ego, and we fall under its spell. It is not a spoiler to tell you that things turned out well for Pam Royes; the pleasure of her story comes in the unexpected turns along the way. The question that animates her recollection — who was that young person, that stranger, who so long ago set out on the fateful journey that led to this moment in time? – is the smallest of queries and also the largest, and as we accompany this personal exploration of a most unusual life, we will undoubtedly have insight into our own.

![]()

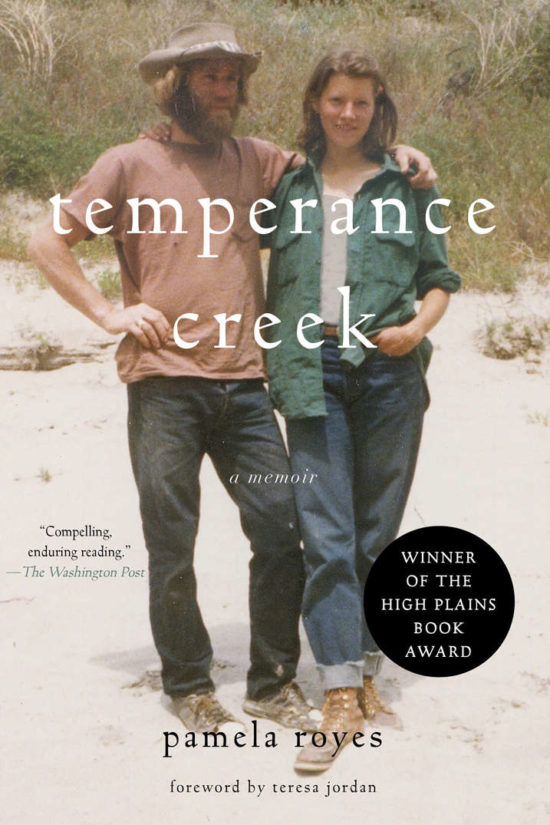

Temperance Creek by Pamela Royes is available from your local independent bookseller, Amazon.com, and Barnes and Noble.